I’m often asked if Meridian has an official Change

Management methodology. The short answer

is No.

I fear methodologies force-fit the same activities on every

situation. That does not work.

Instead we’ve distilled a set of principles that accelerate

the adoption of new methods, processes, and technologies.

1. People

Follow The Path of Least Resistance—So Your Desired Goal Had Better Be On It

People naturally seek the Path of Least Resistance--the

pathway that provides the least resistance to forward motion. A person taking the path of least resistance

seeks to minimize personal effort and/or confrontation.

It’s imperative to

credibly demonstrate how proposed change(s) are on the Path of Least Resistance—that is, how

a new technology is easier to use or offers more “reward” than current

approaches (“reward” in this context has many definitions, not just money).

Painting the picture

that a “new and improved” process or technology is easier to use is a bit of an

art. You can’t just say “this is better,

trust me”—people must come to the conclusion themselves. Hands-on exposure to the new methods or

technology is necessary. Success stories

that explain how the new method is easier and better help. Credible supporters who point out how the new

approach is on the right path are a requirement (see my next point).

Despite your efforts

a better approach can struggle to gain traction. In this case it’s proven effective to

directly ask “Why won’t you adopt our new approach? Why isn’t it better than our current methods? What will it take to get you to switch?” It takes some courage to ask these

questions—you might find that your next great idea is miles off the Path of

Least Resistance—but it’s better to know.

2. Tap

The Power of PEERS

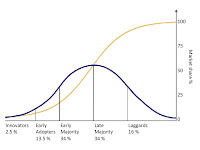

I am very interested

in the science of Diffusion—understanding how innovations spread through a

population. A core beliefs in Diffusion

science is The Principle of Homophily (Homophily = "Love

of the Same"). Homophily is the

tendency of individuals to associate and bond with people who are most

like them. Homophily plays a powerful

role in the adoption of new practices because we learn best from someone who is

like us.

I am very interested

in the science of Diffusion—understanding how innovations spread through a

population. A core beliefs in Diffusion

science is The Principle of Homophily (Homophily = "Love

of the Same"). Homophily is the

tendency of individuals to associate and bond with people who are most

like them. Homophily plays a powerful

role in the adoption of new practices because we learn best from someone who is

like us.

Homophily means it’s

imperative to find your experts amongst the population you are trying to

change. It’s important to ensure any and

all contractors who are engaged to help you change are most like your own

people. It’s better to actually grow

your own Change Leaders, selecting and supporting a sub-group of your people

who score high on familiarity to lead your change.

3. There’s PRIORITY & POWER, And They Aren’t

Owned By The Same People

Adoption happens when it is clear that acceptance of the new

is a real organizational priority and equally that the person who has

immediate power over me allows or encourages adoption. Senior

executives foster adoption by lending their personal credibility to programs, deciding

which programs control the best resources, and determining the professional

gains accruing to contributors. But

“executive priority” alone will not ensure adoption.

Adoption happens when it is clear that acceptance of the new

is a real organizational priority and equally that the person who has

immediate power over me allows or encourages adoption. Senior

executives foster adoption by lending their personal credibility to programs, deciding

which programs control the best resources, and determining the professional

gains accruing to contributors. But

“executive priority” alone will not ensure adoption.

It’s rarely

acknowledged but true: Individual

contributors who have been asked to change how they work need the permission of

their immediate supervisor to make this change.

This ‘permission’ is subtle—I’m not going to ask, “Gee, can I use this

new accounting system?” but it will be abundantly clear to me whether use of

the new system is what the person who holds power over me wants or does not

want. Mid-management and supervisors

thus wield considerable power during times of change. Every successful change program must

understand and manage mid-level support for the program.

4. Never

Underestimate The Problems of the PAST

Expectations for current success are always based on

perceptions of past efforts and outcomes—even if those past efforts and

experiences are not directly applicable.

Think of your company’s history: How many projects were

regarded as disasters? How often do

people mention these disasters when a new project is

introduced?

In our work supporting clients striving for business change skepticism

about past efforts has material impact on support at least 80% of the time.

A major study we completed contrasting a sample of

successful and unsuccessful corporate initiatives showed that perceptions of

past support for projects was the second most important determinant of program

success (expectations for rewards was the most important determinant).

Common sense strongly suggests a history of past failures colors

future plans, leading people to wonder, “So what’s different this time?”

Common sense strongly suggests a history of past failures colors

future plans, leading people to wonder, “So what’s different this time?”

And that’s precisely the point. You must understand how people view past

projects. And you must credibly explain

what’s different this time.

Many organizations want to bury the past. They regard it as ill-mannered to mention

past failures. They fear mentions of past

projects will somehow compromise people’s support, as if organizations lack

collective memory.

Not advised. It’s

important to allow people to express skepticism about past projects, within

bounds. It’s imperative to credibly and consistently show people how

this effort is different, and especially how this program’s results will differ.

5. Sustain “Offensive” Support

Support equals the people and processes that move people

from current practices to better processes.

Support usually happens after a problem occurs, rendering

the support reactive or defensive.

Effective support should be “Offensive,” committed and to

nipping problems early, often, and before they escalate.

“Offensive” support means telling people what is changing

and why, addressing “what this means to me,” allowing errors during adoption,

and providing mechanisms for eliminating errors over time. Support should start early in the program and

should sustain well past the formal “completion” or Go Live point.

Some examples of Offensive support include group and

individual Information Sessions, Self-Guided Change Discussions, and increasingly

online communities and forums. Change

Agents are critical—successful programs always deploy networks of people who are

trained and tasked with providing hands-on, grass-root level support and

leadership during times of change.

In Summary

Years of work supporting diverse change programs revealed

the Five Principles we use to accelerate adoption of new technologies and

methods.

So I encourage you to consider all five when plotting your next

organizational initiative.

But remember: While the principles are universal, the

actions derived from them are always situational. One size never fits all.